In Kenya, some foreign economists thought it wise to disconnect some residents of a Nairobi slum from access to public water supply to test the hypothesis that – drumroll- it induces landlords to pay water rates.

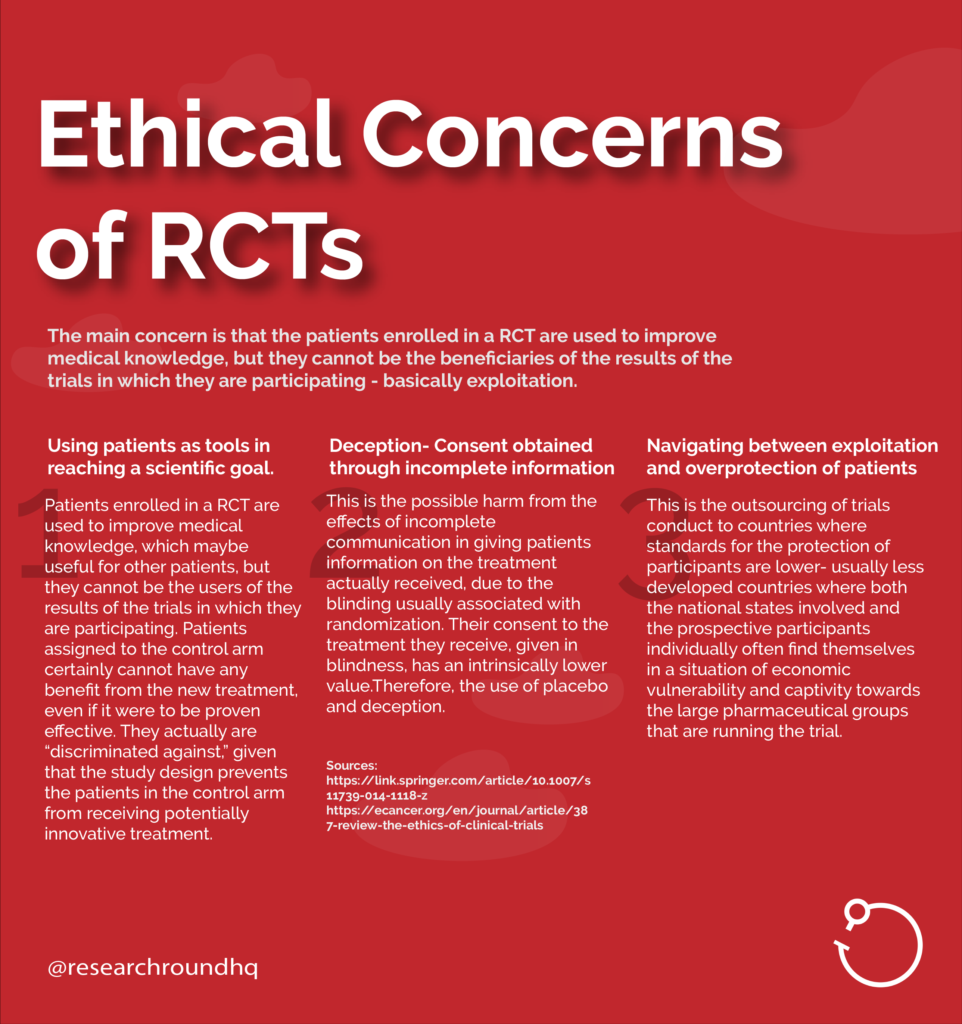

Randomized Control Trials (RCTs) is an experimental design that has curiously become popular with American and European social scientists in studying Asian and African subjects in recent times. Messrs. Aidan Coville, Sebastian Giliani, Paul Gertler and Susumu Yoshida in their paper titled Enforcing Payment for Water and Sanitation Services in Nairobi Slums published by the National Bureau of Economic Research did not consider if the goal of the research – confirming if the disconnection of public services induces payment of water rates – warranted the discomfort that the random residents of the Nairobi slum had to go through. They simply could have been asked but their feelings were not important enough for the researchers.

Randomized Controlled Trials (RCT) is a method that is fraught with ethical landmines in the hands of the best researchers. It is dangerous in the hands of unscrupulous researchers without regard for the humanity of their subjects. Tragedies abound in Africa of the evil that RCTs have caused. The victims of Pfizer’s test of the efficacy of their meningitis drugs trovafloxacin (Trovan) in Northern Nigeria, among others, come to mind.

Sir Angus Deaton, the 2015 economics laureate who was awarded the prize for strengthening the use of empirics in microeconomic analyses, in his paper Randomization in the tropics revisited: a theme and eleven variations warns those who are keen to join the bandwagon of experimentation in economic analyses that a method is not by itself superior to any other, not even Randomized Controlled Trials (RCTs) that he made popular.

According to Sir Deaton, RCTs have been used in Economics for more than fifty years and have grown in popularity in the last two decades especially in development economics. The 2019 Sveriges Riksbank prize in Economic Sciences in memory of Alfred Nobel awarded to Abhijit Banerjee – author of Poor Economics – Esther Duflo, and Michael Kremer for their use of carefully designed experiments (RCTs), to obtain reliable answers about the best ways to fight global poverty seems to have bolstered the confidence of the randomistas. Bolstered on by popularity and a prize, randomistas have ignored Deaton’s advisory that RCTs have no unique advantage or disadvantage over other empirical methods, but it seems old errors are quickly forgotten and often repeated by recent researchers.

No RCT can ever claim to have legitimately established causality. The imposition of a hierarchy of evidence is bad science and dangerous because it discounts context. That something is observed among a certain population does not make that observation correct in another population.

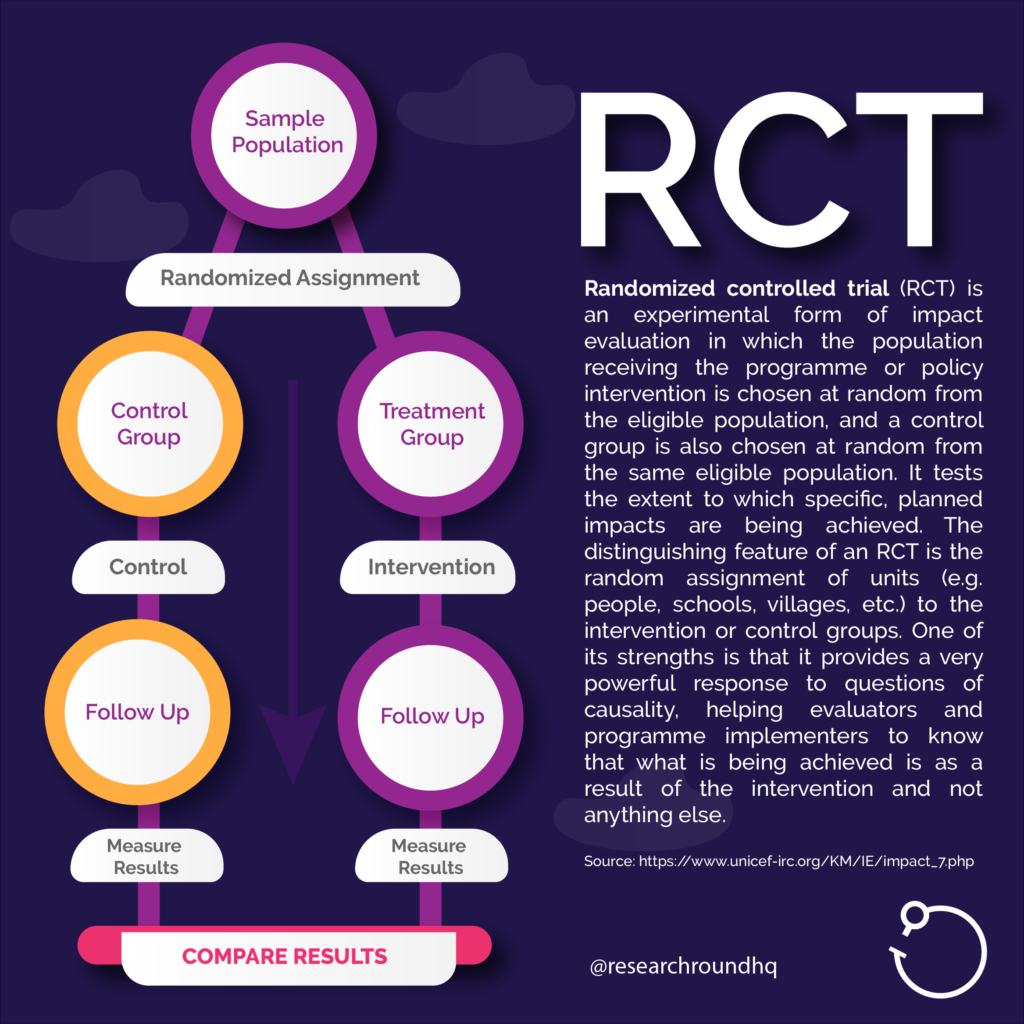

RCTs suggest that by introducing a treatment to a control group and the experimental group one can easily infer that the treatment caused the observation. Correct inferences are neither that simple nor straightforward. This is the grievous error that is often contained in a lot of World Bank advisory for developing nations. Trials cannot establish the truth.

That RCTs are more rigorous and more scientific than other methods are false. Licensing medicine through RCTs also does not make RCTs any more scientific. An example was the licensing of prescription opioids like OxyContin resulting in the death of thousands in America.

Development economics is replete with studies that aim to “find out what works”. Only that institutions matter and the common caveat of ceteris paribus, all other things being equal, are often ignored. That it has worked for one group does not guarantee that it will work for another group. We should take advice from Bertrand Russell’s chicken and be wary of Bill Gates’ chickens. Bertrand Russells’s chicken learned from hundreds of replications that when it heard the farmer’s footsteps she was about to be fed until Christmas when the farmer cut her throat. That farmers in some Ivorian community prefer chickens to cash does not mean other communities around Africa do. It is not enough that it is free chicken nor that it is offered by ‘expert’ advice.

Economics is notoriously called a dismal science for a reason. The wrong deployment of RCTs will not let economists, or any other researcher who wrongfully deploys RCTs, live down this sinister appellation.

Therefore, experimentation by the random selection of a person to land a blow on is bullying, not good science. It does not matter if the reaction confirms one’s hypothesis or not.

Written by Ajibola Adigun for ResearchRound.